History as Understood from the Psychology of Victims and Perpetrators

The hardest part in understanding the nature of evil is to first recognize that you or I could, under certain circumstances, commit many of the acts that the world has come to regard as evil.

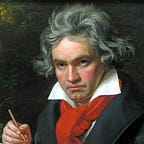

— Roy F. Baumeister

It is George Santayana, a writer and philosopher, who stated that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Winston Churchill, in a 1948 speech in the House of Commons further reiterated Santayana’s words that indeed doomed were those who failed to learn from the past. These luminaries highlight the centrality of history not only in our lives but also in our societies. The quotes are cliches today and all people, driven by disparate motivations to either repeat or not repeat history, have found themselves buried in tomes of historical works, all in a bid to learn it. But history is not a clear cut science where facts reign supreme. As this essay will endeavor to demonstrate, our understanding of history is often shaped not only by its authors but also by our personal prejudices depending on where we stand in the long narrative of time.

The Writers of History

Historians, unlike scientists and other academics, have an interesting job description that most often does not involve the direct interaction with their subjects or the events they study. A physicist can very quickly design an experiment, a medical researcher can conveniently enroll a large number of subjects to a double-blind controlled trial, while a psychologist can very easily access the mental processes of his subjects via interview, questionnaires, or fMRIs. For the historian, gathering facts is mostly a deductive exercise and he has to rely on primary sources like a page from an ancient King’s diary, a hip bone from a long forgotten humanoid, or illegible hieroglyphs to reconstruct certain events in time.

The process of deduction wholly depends on the historian’s wit and judgement. Without corroboration or some form of peer review — which also most often depends on the reviewer’s subjective interpretation of the artifacts, what was initially deduced by the historian can easily pass as fact. This is not to mean that all history is fiction, or that all historians are like the famous Heinrich Schliemann who allegedly fabricated evidence of his discovery of the ancient city of Troy. No! Most of history is fairly accurate since using scientific tools and other methodologies like DNA sequencing, dating tools, and corroboration from secondary sources like books from a similar period, historians can develop a fair grasp of the events they study.

Despite that we are still left with a large amount of history that lingers in the gray areas of fact and fiction. Our understanding of history, for example, is affected by survivorship bias whereby only what is salvaged either from decomposition or destruction is documented. Well preserved diaries of kings that survive are more likely to inform our understanding of ancient life compared to peasants who leave nothing behind. In war, the subdued and defeated are least likely to survive long enough or to have ample space to give their versions of the story. Historians thus concede that history is indeed written by winners. It is in this context that I want us to further interrogate the nature of history from the perspective of both winners and losers and to show you that while most of history is not false, in most instances, our accounts of events might be far from the truth.

Winners and Losers: The Winner’s Story

The history of the world, especially where war is involved, tends to have both winners and losers. I will refrain from using the word losers in favor of ‘victims’ which is modest and politically correct. I will also refer to the winners, though unfairly, as ‘perpetrators.’ This distinction is informed by the fact that modern understanding of history and its accompanying political discourses tend to view the last half a millennium as a period when the winners perpetrated violence against losers, who allegedly were victims of the aforesaid atrocities. As winners, perpetrators wrote a history that most descendants of victims largely disagree with. In their counter-narratives, victims elucidate their different recollection of events and endeavor to write a history that is markedly different from what came from perpetrators. To the student of history who is eager to learn it so as not to repeat it, this should definitely be a problem. A problem that can only be solved through an earnest interrogation of the psychologies of perpetrators and victims.

Roy Baumeister is a psychologist and social scientist who has studied the nature of evil and the people who perpetrate it. Since most historians will admit that some actions committed in history can be classified as ‘evil’ including slavery, colonialism, and violence against native communities, Baumeister’s framework lends a lot to this analysis. The Nazis for example,were the archetypes of evil. Questions linger of what could have caused ordinary individuals to conduct systemic extermination of millions of people, and whether Nazis regarded themselves as evil?

The Nazis never thought what they were doing was evil. As Baumeister observes, most of them believed they were doing good. The Third Reich was on course to become a perfect society or a utopia, only that Jews and gypsies were standing on the way. The need to do good and build a perfect society was enough to convince ordinary individuals to commit heinous crimes. Righting past wrongs, Baumeister argues, was also a sufficient reason that convinced ordinary Germans to round up and exterminate Jews. It was believed Jews had “undermined the war effort and stabbed their country in the back, and the allied enemy powers, unable to win on the battlefield, had cheated and then exploited Germany.” This understanding of Germany and the Nazis is a window into the nature of evil and what exactly goes on in the minds of those who commit such atrocities.

Like the Nazis, perpetrators of historical crimes such as slavery and colonialism had a different understanding of their actions. First, perpetrators do not see their actions as evil, and second, they are most likely to “ignore or downplay the moral dimensions of their actions.” Baumeister argues that “evil exists primarily in the eye of beholder, especially in the eye of the victim.” It is the victim who captures the horrors of the heinous crimes committed towards him. To the Europeans and American colonists, slavery might have been a matter of economic necessity and a justified strategy to build and advance the needs of the new colonies. But to the slave, the horrors of disease in the rice plantations of Lowcountry and the whippings and long hours in the Sugar plantations of the Caribbean were signs of moral depravity from callous masters.

Even though white people eventually recognized the immorality of slavery and endeavored to abolish it, their actions had demonstrated the tendency for perpetrators to downplay or ignore the immorality of their actions. To black slaves, it was unfathomable how supposedly religious people who had earlier introduced them to Christianity would commit such atrocities. But history is written by winners and in the case of imperialism, colonization, and slavery of the last five hundred years, the history was written by white people. It is therefore not uncommon to find that the history written of that period either underplays the seriousness of those evils, justifies them, or ignores the lingering moral questions. It is in recognition of this tendency among perpetrators to distort the seriousness of their actions does Baumeister observe that “the question of evil is a victim’s question.” Without input from the slaves, the colonized, and other conquered peoples, the winner’s story isn’t the full story.

The Victim’s Story

Victims play a very vital role in the great narratives of history. They are at the receiving end of evil actions and most of them either die, are maimed, or subjugated. Even worse is that their voices are never heard because either they’re deliberately muzzled or because their stories become part of what gets destroyed or lost in time. Of the victims, Baumeister argues that “the very enormity of a crime is itself a victim’s appraisal, not a perpetrators.” It is also more likely that victims will continue to have fresh memories of crimes committed towards them even as perpetrators forget or deliberately ignore them.

Louisiana, in 1863, reads as follows: “Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. My master come after I was whipped; he discharged the overseer. The very words of poor Peter, taken as he sat for his picture.” Source: U.S. History Openstax.

However, when victims are given the chance to recount a perpetrator’s actions, Baumeister argues that there’s a general tendency for them to distort the facts. Victims will generally reshuffle and twist facts “to make the offense seem worse than it was.” This is the direct opposite of what perpetrators would normally do, which is to underplay or lessen the seriousness of their actions. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is a historian, writer, and activist who wrote “An Indigenous People’s History of the United States.” The book is a parallel history or a counter narrative of the American history presented in school text books like “The American Yawp” or “The U.S History Openstax.” Ortiz’s version of American history is what I would consider a victim’s story since it narrates in detail the horrors meted upon Native Americans. In one swoop she likens colonialism in America to genocide arguing that:

The history of the United States is a history of settler colonialism-the founding of a state based on the ideology of white supremacy, the widespread practice of African slavery, and a policy of genocide and land theft…Inherent in the myth we’ve been taught is an embrace of settler colonialism and genocide. The myth persists, not for a lack of free speech or poverty of information but rather for an absence of motivation to ask questions that challenge the core of the scripted narrative of the origin story.

Ortiz acknowledges the limitations of mainstream history courses which fail to adequately capture the “victim’s side of the story” or to challenge scripted narratives of perpetrators. To her, colonialism in America was nothing short of genocide since through settler colonialism, natives were either removed from their lands or killed. A search of the word genocide in the Openstax U.S History textbook only yields five hits; three unrelated to Native Americans and two claiming that “some scholars view the resulting loss of Native American life as a clear example of genocide in the United States.” Unlike Ortiz who believes settler colonialism was a genocide, the text book is more cautious, referring to the events casually as “loss of Native American life” and that only “some scholars” would describe the events as genocide.

It is hard to tell where the truth lies in both historical accounts. Clearly, from the language and tone Dunbar-Ortiz uses to write the book, one can read from the fine print a sort of activism and an attempt to exaggerate the seriousness or significance of events. The question of whether European presence in the Americas was genocide can be looked at from different perspectives. First, by acknowledging the fact that most Native Americans died of disease, and in some instances, they were murdered due to their active participation in battles such as the French and Indian wars. Second, the world before World War II wasn’t ruled by liberalism and indigenous tribes were themselves warring societies. The rule of conquest was the defining order. Ortiz’s description of indigenous history, therefore, is understandably a product of his positionality as a victim. According to the Wikipedia, Dunbar-Ortiz appears to be struggling with her identity, with little clarity as to whether she’s a Native American or not. It states that Ortiz was:

The daughter of a sharecropper of Scots-Irish ancestry and a mother that Dunbar believes to have been partially Native American, although her mother never claimed to be Native and Dunbar-Ortiz grew up without any Native heritage. Dunbar-Ortiz initially claimed to be Cheyenne but she subsequently acknowledged being white. She now claims that she is Cherokee and that her mother denied her Native roots because she married Dunbar’s father, a white tenant farmer.

But if settler colonialism was genocide as Ortiz argues, then British actions in many parts of the world were genocidal acts too. In Kenya, the British settled in the ‘white highlands’ where the soils were fertile and ejected local communities. Caroline Elkins writing in her book the “Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulags in Kenya” narrates the events that proceeded British colonialism in the country including the murder of thousands of Mau Mau fighters and the detainment of a large majority of the local communities in concentration camps. But Elkins rarely uses the word genocide and it only appears thrice in the whole book. In one instance she writes;

I now believe there was in late colonial Kenya a murderous campaign to eliminate Kikuyu people, a campaign that left thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands dead.

As a white woman, a non-Kenyan, and definitely not a victim in the story she writes, her words are not as heavily loaded as Ortiz’s. Words like “campaign,” “murderous,” and “eliminate” are used to create dramatic effect but not in the way a word like “genocide” would. Her inclusion of the phrase “perhaps hundred of thousands” after the official figure of deaths in the thousands, is also an exaggeration that serves to counter what seems to her as few deaths. From a total population of 1.5 million which she cites as the total population of the Kikuyu, hundred of thousands of deaths would comprise more than 6% of the Kikuyu population at the time. For a country with less than 8 million people in the 1950s and 60s, these numbers of death would be genocidal. Many educated Kenyan’s believe Elkins’ history even though she’s white and American. The reason is because she tells the story as the victims would want it told; with a little touch of exaggeration here and there. (Read the notes section below for more on Elkins book).

Victim Signalling in Modern Societies

Baumeister, in his analysis of evil and the way victims and perpetrators describe it, opines that “one cannot rely on either the victim’s story or the perpetrator’s; the reality may lie somewhere in between. No one’s story can be trusted in a scientific sense,” even though much of our history contains accounts and narratives from either of them. Since World War II, the frequency of wars has declined and the world has become largely peaceful. This makes it unlikely that countries will attempt to dominate one another or that previous victims and perpetrators will want to settle scores violently. The result is a rise of victim signalling whereby previously colonized, enslaved, or subjugated groups try to extract material gains from perpetrators by broadcasting their oppressed status.

A paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology defines victim signalling as “a public and intentional expression of one’s disadvantages, suffering, oppression, or personal limitations.” This strategy facilitates “nonreciprocal resource transfer from others to the signaler.” Unlike the past where victims were seen as individuals with lower esteem and self-respect, modern societies are different with louder and more assertive signalers gaining more social status and higher material wealth. Intensified calls for reparations is just one of the many ways in which victims seek to benefit from this unidirectional transfer of resources and wealth.

The authors also identify the virtuous victim effect which shows that victims are more likely to be viewed as moral by others. Even when some are not entirely good people, victim signalers tend to get the benefit of doubt and are cast in better light. This discourse has deep ramifications on how history is written and how we come to understand it. Depending on who is the victim, there is always a deliberate attempt to describe events in ways that either cloud the facts or exaggerate the virtues of the victim. In the same fashion as Ben Simon observes in the Stanford Review, even perpetrators may seek to exploit this system and may sometimes come to view themselves as oppressed. To the historian, this quagmire presents a much bigger challenge since as Baumeister argues “one would need objective evidence against which to compare the stories of victims and perpetrators, and such objective evidence is not often available.” It is not even clear what objective evidence for historical analysis would look like.

Conclusion

Our understanding of history is therefore bound to vary depending on our motivations when reading it or the prejudices of the authors as they write it. If our passions are whipped up because of our positionality as victims, then chances are we will enjoy the highly exaggerated versions of histories written by victims. Our understanding of the facts will be clouded by the author’s use of verbose language and pesky adverbs and adjectives. In the same fashion, and in the quest for neutrality, perpetrators are likely to underestimate the importance of some facts and result to what Dunbar-Ortiz calls “spouting platitudes.” The richness of history gets lost in mundane details and half-stories written by perpetrators. Without objectivity and facts, most students of history including those who make a deliberate attempt to learn it, are condemned to repeat it.

Notes:

- Caroline Elkins’ book includes in the title the word “gulag” which is Russian for forced labor camps. It is a big word considering what we know of Russian camps after the Bolshevik revolution. In the book she also makes use of the word “concentration camps” which were popular in Nazi Germany.

- While reading the book I decided to ask about these camps in Central Kenya and I was lucky to get information of a person born in the 1940s and who lived in one of the villages Elkins alludes to when she writes that the:

- “British did detain the women and children, though not in the official camps but rather in some eight hundred villages. These villages were surrounded by spiked trenches, barbed wire, and watchtowers, and were heavily patrolled by armed guards. They were detention camps in all but name.”

- The lady whom I will call Jane agreed that there were indeed villages where a large group of people, mostly women and children, lived. Like the Ujamaa villages of Tanzania, these villages were communal in that the people who lived there worked together on firms and the produce harvested would be shared equally among them.

- I asked Jane whether the villages had been established by the British and she said no. From her story, the British lived in Nyeri town and rarely went into the villages. The Mau Mau were still in the forests and the British would fight them there. But she agrees that the Mau Mau would come at night and would find food already prepared for them by some of the women and set aside in a specific hut. They would eat and leave before dawn and many people in the villages never met them face to face.

- She also says that the villages were not patrolled (explains why the Mau Mau would come at night), and there’s no hint of barbed wires, watch towers, and spiked trenches. The women could get out of the village at will to access the farms.

- Jane also acknowledges the presence of Kikuyu home-guards whose presence in the villages led to a lot of secrets (explains why the Mau Mau would come unnoticed and leave without trace).

- So what do we make of concentration camps and gulags alluded to by Elkins? Worth noting is that there were real detention centers that functioned as prisons and which I believe is what Elkins would call concentration camps. And what of the gulags? Were these villages gulags? I do not know. I believe this single story cannot invalidate whatever she was told by others. I will ask more people about this issue and try to get a rough understanding of the events.

- However, writing a victims story as Elkins’ does might have prompted her to exaggerate the facts. These villages weren’t anything close to what was in Russia or Nazi Germany. The respondents she visited might also have exaggerated their narratives after seeing she was white. She says people confused her for British and others even refused to talk. For those familiar with ethnography, going around asking people things might not be the most accurate way to collect data. Respondents have a tendency of telling researchers what they want to hear especially if she’s alien. I also wonder how much got lost in translations; and more specifically, how words like gulags and concentration camps were translated.